What are the potential economic and energy consequences of using Bitcoin and altcoins as central bank reserve assets?

In recent months various cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin and Solana, have been at the centre of attention as they were considered by various countries for inclusion in their central bank reserve asset list, but one may question the relevance of this decision.

Reserve assets are used by central banks to stabilise the exchange rate of their national currency, as they allow for buying back circulating liquidity in case of a price decline, balancing supply and demand. Traditionally, gold has played the role of a reserve asset, given the confidence in its value during times of economic crises.

This trust in the value of gold relies on two characteristics that explain its use as a medium of exchange for millennia. First, it is not replicable (so far, no alchemist has been reported to have successfully turned lead into gold 😊). Second, given just a few grams have a high perceived value, as it is rare on Earth, it is easy to transport in the context of a trade.

These two characteristics of gold are shared by Bitcoin, as it is not replicable since its supply is limited by design to 21 million coins, making it rare, and as it is an efficient method of transaction for not requiring any other means of transport than the internet network for a transfer; which moreover lasts just few seconds, compared to days with traditional bank transaction means like SWIFT.

It is these similarities between gold and bitcoin that have led to Bitcoin being considered as a central bank reserve asset, and later other cryptocurrencies. Moreover, some countries see another benefit of this adoption by betting on Bitcoin’s long-term value increase.

Nevertheless, this reasoning is not free from potential risks:

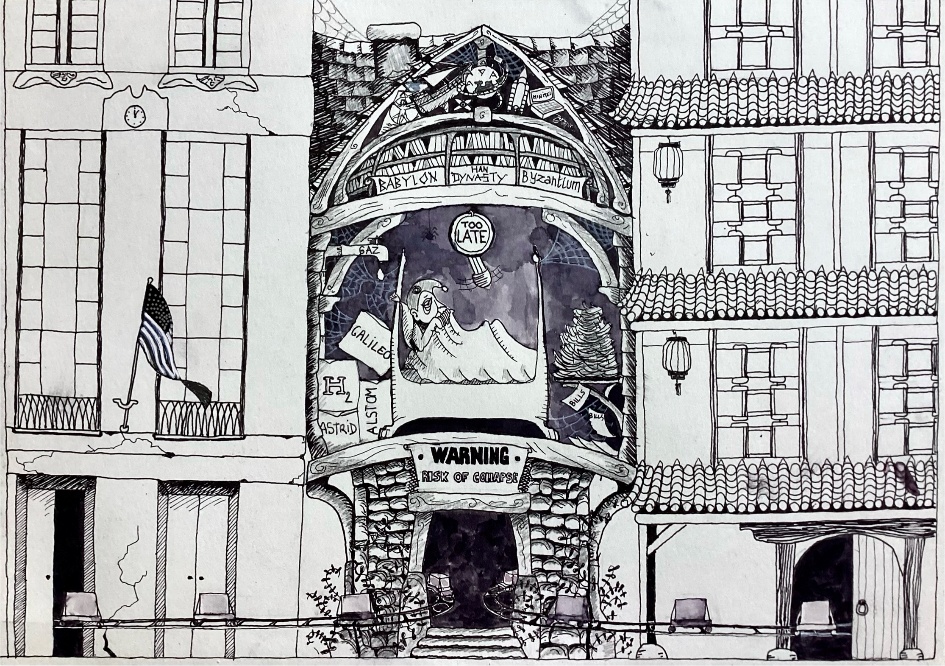

- First, if Bitcoin is indeed non-replicable, it is at the current state of technology, and there is no guarantee that the Bitcoin blockchain will remain unbreakable, many considering, for example, the future cryptographic decryption capabilities of quantum computers.

The day Bitcoin is reported to be hacked, its value will immediately fall to zero. That would put at risk the value of national currencies backed by a significant proportion of Bitcoin within their central bank reserve assets. It could lead to inflationary crises, even potentially followed by economic collapses in the worst-case scenarios.

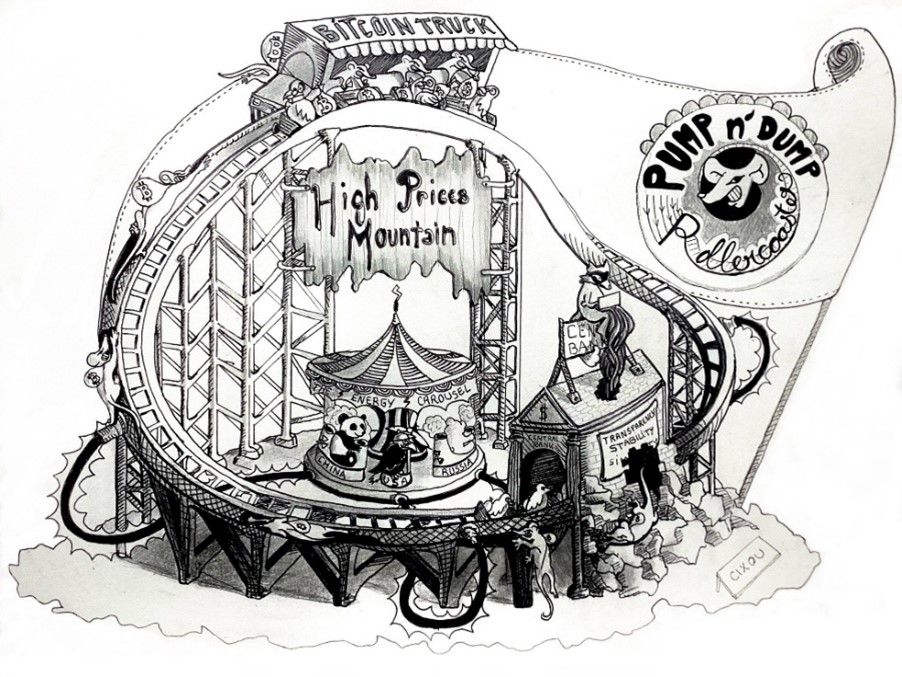

Moreover, even if Bitcoin were not hacked, it would only take a credible rumour about its fallibility for its price to drop. The same would happen with other cryptocurrencies. - Cryptocurrencies are subject to price manipulation by private actors, who would thus have the ability to influence central bank behaviours through impacts on their reserve asset value. In fact, Bitcoin holdings are increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few institutions, now reaching sometimes several percent of the overall supply.

Indeed, cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, show high price volatility, resulting from low liquidity in their markets. For example, a low liquidity in Bitcoin means that it is not possible to buy or sell large amounts of this cryptocurrency without affecting its price, unlike gold. Therefore, we can observe “Pump and Dump” schemes with cryptocurrencies, where a player buys a significant quantity of a coin, creating upward price momentum, and then takes profits by selling its wallet at a higher price, causing a price drop. This loop can be repeated indefinitely, generating endless undue gains. Moreover, this behaviour would be hard to regulate, cryptocurrencies being decentralized by nature, and only if we were ever able to prove a move was deliberately a Pump and Dump one.

It is possible, however, that this liquidity will increase in the future, decreasing the Pump and Dump risks. Nevertheless, there is a certain level of contradiction in expecting central bank purchases to increase this liquidity, if they choose to adopt a long-term holding strategy.

- If gold is used as a reserve asset, it is also because of its historical negative price correlation with stock markets. It makes gold a hedge against financial crashes. This is particularly useful for central banks, since, as discussed, they aim to protect their asset value from market volatility to be able to back their national currency.

Until now, Bitcoin and altcoins have not shown a similar negative price correlation with stock markets. On the contrary, for now, a stock market drop usually triggers a Bitcoin crash. It is unclear whether this situation will persist and some hope for a reversal, but it remains a speculation. It creates additional risk for central banks if they substitute some of their gold holdings with Bitcoin.

In addition to the economic risks of incorporating cryptocurrencies as central bank reserve assets, it is also worth mentioning that Bitcoin is not necessarily the best choice among all cryptos to play this role, because of its intense energy consumption.

Indeed, Bitcoin transactions are validated using a proof of work protocol, whereas more recent blockchains are using a proof of stake protocol ten thousand times less energy-intensive (*1).

The proof-of-work protocol consists of choosing Bitcoin infrastructure managers, to reward for their services (miners), according to how fast they solve mathematical problems. This competition is set up for the validation of each block, which regroups multiple transactions, and the reward is delivered in Bitcoin. The idea behind this protocol is to make it almost impossible to corrupt the blockchain state by simultaneously modifying multiple previous blocks, given the computational power that would be required.

This competition has led to a steady increase in miners’ computing power, and thus of the energy consumption of the Bitcoin blockchain:

- In 2014, Bitcoin’s electricity consumption was estimated at a few TWh (*2).

- In 2024, it was estimated to 176TWh (*3). By way of comparison, the annual electricity production in France is around 500 TWh.

On the other hand, the proof-of-stake protocol randomly selects block validators from cryptocurrency holders but favours those with the largest amounts. In this way, holders have limited incentive in corrupting a network in which they themselves are financially invested.

The Ethereum blockchain has migrated from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake in 2022, reducing its energy consumption by 99.99%:

- In 2022, its yearly consumption was around 94TWh (*1).

- In 2024, it was close to 0.01TWh (*1).

The energy consumption of Bitcoin leads to two consequences that must be considered during the decision to select it as a reserve asset by central banks:

- Its proof-of-work protocol constitutes a waste of energy, in a context of energy scarcity. While some argue that Bitcoin’s energy consumption is largely sourced from renewables or otherwise unused resources, and that the heat generated by mining operations can be partially recovered or even support economic development in remote areas, these claims strike me as rather unconvincing. Indeed, any amount of energy consumed for unnecessary calculations leads to losses of efficiency in any case, and the investment required to produce this energy could be allocated more wisely.

- It creates a rent-seeking situation for countries with low electricity prices, and they might not wish for Bitcoin’s transition to proof of stake. Moreover, Bitcoin does not have a foundation at its helm that can manage this transition, as Ethereum does.

In addition, it is uncertain if countries hosting Bitcoin mining could not be tempted to regulate these activities to temporarily influence the coin price, and thus central bank reserve stability.

In conclusion, it is likely that the use of cryptocurrencies as reserve assets will increase the risks of economic instabilities originating from central banks, in addition to representing a significant waste of energy in the case of Bitcoin.

The only benefit for central banks would be an increase in their crypto assets in the long term, but market speculation is normally not the role of these institutions. On the contrary, they are normally supposed to provide macroeconomic stability through the monitoring of their respective national currency.

I am not against cryptocurrencies, quite the opposite, I think blockchain technology has already provided and will keep providing opportunities for innovation, due to its decentralized nature. I have actually proposed new use cases myself in previous articles, towards climate risks, and towards carbon offsetting & air quality. Nevertheless, I think exposure to cryptocurrencies at a state level could be managed by public investment banks, but not by central banks.

Do not hesitate to contact TXEM if you have any questions.

Sources:

*2: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/bitcoin-energy-use-mined-the-gap/

*3: https://ultramining.com/news/en/bitcoin-networks-energy-consumption-reaches-176-twh-per-year/