Why might European countries’ capacity to restart their economies be unprecedentedly low in the event of a future financial crisis?

Financial crises are a recurring phenomenon. Whether some can be avoided or not, states need to be financially prepared, and their economies need to be strong enough to recover on their own after a financial shock, or at least be able to restart through government financial stimulus. However, there is legitimate doubt that European economies will be able to cope with the next crisis, due to factors such as the decline of industrial monopolies, depletion of energy resources, and the accumulation of sovereign debts.

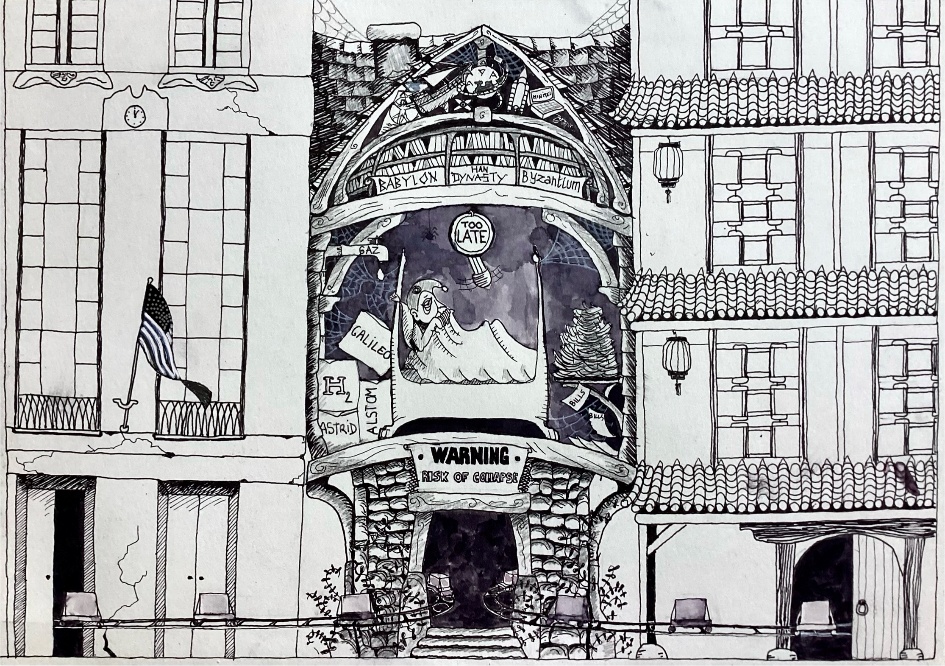

The knowledge circulation and the erosion of European technological monopolies

As a whole, disregarding occasional improvements in some countries, the economic area composed of states currently using the euro has experienced a steady decline in economic growth since the 1970s.

The 1970s oil crises contributed to the start of this decline, but another factor is the gradual loss of Western Europe’s industrial leadership.

Knowledge has circulated throughout the centuries. Western Europe owes part of its economic dominance to the influx of scientific knowledge from the declining Byzantine Empire, which itself benefited from the discoveries of earlier civilizations. This exchange contributed to the onset of the Renaissance and Europe’s subsequent scientific and industrial dominance.

The flow of knowledge continued, and especially after the mid-20th century, industrial outsourcing, favoured by deregulation, and new communication technologies reduced the exclusivity of industrial knowledge. There is no longer a need to wait for an event like the fall of Constantinople to access scientific treatises; for example, many PhD theses are now readily available online.

Therefore, Europe has lost much of its industrial leadership over recent decades, notably in sectors such as automotive and aerospace. Moreover, only a few European companies still hold industrial monopolies, like ASML in lithography, for example. Consequently, there is no longer any guarantee that Europe can easily sell its production, as more competitors are present in its markets or have surpassed it technologically.

In this context, where knowledge is more evenly distributed, access to energy and related costs become even more critical factors for industrial competitiveness.

To make Europe’s situation worse, some of its major Oil & Gas production sites have recently become depleted, such as the Dutch Groningen gas field, which was shut down in 2023, leading to increased dependence on fossil fuels. As I warned in a 2017 document (available here), there was a significant risk of impoverishment and loss of competitiveness for Europe, especially compared to the United States, whose industry often operates in similar sectors. Since 2022, we have indeed observed more European industrial companies redirecting some of their investments to the US to avoid the impact of rising European gas prices.

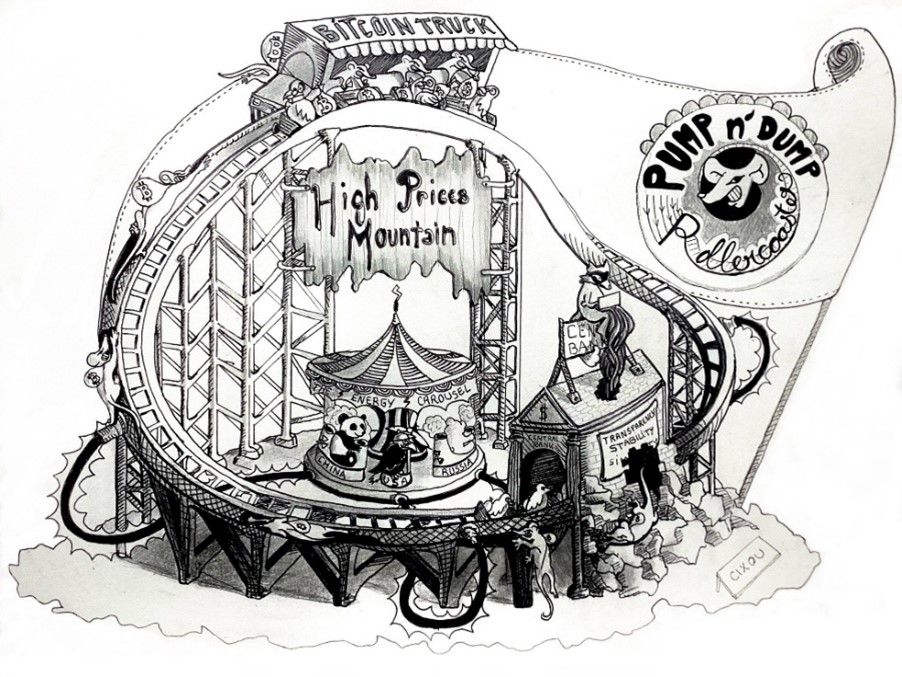

The Expansion of European Debt

From the 1980s onwards, various countries began injecting public funds into their economies, hoping to stimulate growth, which resulted in an increase in public debt. However, these efforts did not fundamentally reverse the decline in Europe’s competitiveness.

By 2008, when the subprime financial shock reached Europe, the budgetary situation of some of these countries made it difficult to finance an economic stimulus policy, leading in 2010 to the European debt crisis through rising borrowing costs, particularly for Portugal, Italy, and Greece.

A debt default could have paralyzed their economies in the long term, as devaluing their national currencies to refinance debt was no longer an option within the Eurozone. Consequently, borrowing costs for other countries could also have risen, as investors would have started to factor in the risk of a eurozone breakup.

That is why the ECB took the unprecedented decision to indirectly finance these debts by purchasing some of the affected countries’ bonds on the secondary market, that is, from their creditors. This increased demand for the bonds and consequently lowered their borrowing costs. Furthermore, the ECB reinforced its bond-buying program during the COVID-19 period, as governments were massively increasing their debt levels. Between 2015 and 2022, the share of sovereign bonds held by the Eurosystem (the ECB plus the national central banks of the Eurozone) rose from 5% to 33%, before being reduced to 25% in early 2025 (*5).

Nevertheless, that ECB policy was not exempt from risks:

- The first risk is that purchasing these bonds requires the ECB to increase the monetary base (M0), often referred to as “printing money.” This, in turn, can lead to an increase in the euro area’s money supply (M3), which represents the money circulating in the real economy. The higher the M3, the greater the upward pressure on prices. In other words, the ECB’s purchase of government bonds to support public debt can lead to rising inflation, as experienced in recent years.

It is also worth noting that although the ECB can reduce M0 in an effort to curb inflation, reducing M3, the money actually circulating in the economy, is considerably more difficult. Moreover, M0 was also expanded to finance corporate debt as part of the quantitative easing programmes.

- The second risk is that the ECB’s purchase of European government bonds, by artificially lowering borrowing rates, creates an incentive for imprudent countries to continue increasing their debt in order to finance economic growth.

Therefore, once the ECB ends its bond-buying programme, as it did in early 2025, these countries suddenly face higher interest rates. This can potentially push them into a downward spiral towards default, driven by unsustainable long-term debt servicing costs.

Unfortunately, this is exactly how France has entered a debt spiral, having significantly increased its debt over the past decade, especially during the COVID period, despite warnings from several economists.

In contrast, Italy, Portugal, and Greece have focused on stabilising or reducing their debt levels since their respective debt crises in 2010.

The current European financial vulnerability

It is now easy to understand that when the next financial crisis occurs, which is only a matter of time, European countries will have a reduced capacity to provide the financial stimulus needed to restart their economies:

- This time, the ECB would likely be unable to finance countries with unsustainable levels of debt without risking hyperinflation, given the current level of M3 and the scale of the debts involved.

- Once European economies need to restart after the financial shock, they will no longer be able to rely on cheap energy, especially following the halt of Nord Stream gas supplies.

- Moreover, the loss of global dominance in the industrial sector would continue to limit economic activity compared to previous decades.

- By contrast, the United States and China could rely on their raw material reserves and industrial strength to facilitate a faster recovery, although in the case of the US, the long-term decline of the dollar’s global dominance could pose a challenge (as discussed in a previous 2023 article, available here).

This financial shock could in fact be triggered by a French debt crisis, through contagion in the financial system caused by potential defaults among French debt holders. Indeed, credit rating agencies are expected to downgrade France, which would reduce demand for French government bonds, as the new rating would no longer meet the investment criteria of certain central banks or pension funds. Rolling over French debt would then become unsustainable, if it is not already. Without at least significant adjustments to the budget structure, this scenario remains a plausible risk.

Following a financial shock, the first possible scenario is a renewed risk of eurozone breakup, with far fewer remedial options than before. This would be compounded by challenges in EU financing, due to shifts among the current net-contributor countries and disparities in their economic situations. The second scenario would be a straightforward desertion of public financing for European countries, effectively masking a bankruptcy.

In any case, the long-term economic competitiveness of European countries would remain a serious concern.

The day after the next financial crisis could be a hard wake-up call.

Do not hesitate to contact TXEM if you have any questions.

Sources:

*1: https://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicateur/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=XC

*3: https://tradingeconomics.com/euro-area/money-supply-m0

*4: https://data.ecb.europa.eu/data/datasets/BSI/BSI.M.U2.Y.V.M30.X.1.U2.2300.Z01.E

*5 : https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2025/html/ecb.sp250611_1~cd38594925.en.html